The following text has been translated from Italian to English by Vivienne Roberts with the permission of the author, Paola Giovetti. The full version in Italian was first published in 1982 as part of Paola’s book Arte Medianica by Edizioni Mediterranee. I would like to thank Paola for her kindness in giving permission for mediumisticart.com to share the art of Narciso Bressanello and enable us to learn more about this captivating mediumistic artist. Copyright of the text remains with Paola Giovetti.

Narciso Bressanello was born in 1915 on the Venetian island of Burano, the third of ten children, from a very modest family. His father was a carpenter who carved clogs and his mother, like almost all the women on the island, was a lace maker. Family life was tough and Bressanello, needed at home to help his parents, only reached second grade in his formal education. At 23, he married and had six children which he supported by working 14 hour days as a labourer and boatman, often finishing late at night by candlelight, and without breaks for Sundays or holidays. For years the family lived in a warehouse, in a single room that served as a bedroom, kitchen and living room.

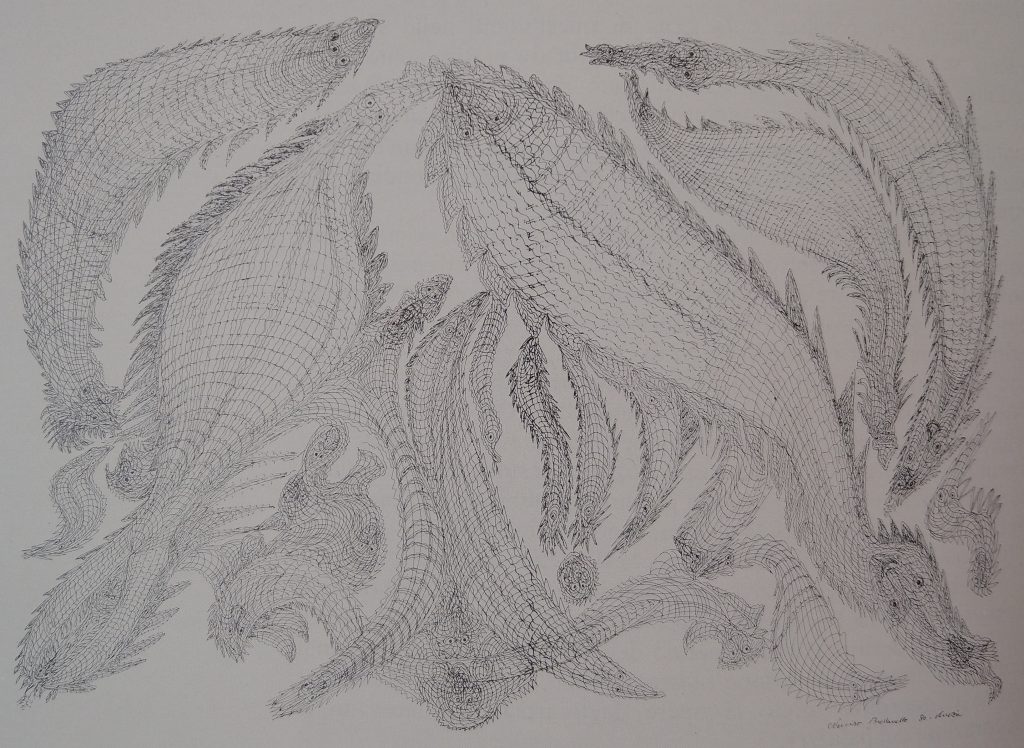

In 1976, probably due to worry and his disadvantaged life, Bressanello was struck by a life-threatening double duodenal ulcer, which affected him for the rest of his life. He spent forty days in hospital followed by a long convalescence at home. During this forced inactivity, he had a sudden and irresistible urge to draw. He procured drawing sheets and markers and began frantically tracing elegant lines which developed into complicated abstract drawings consisting of incredible tangles of dense and twisted lines from which faces, heads of animals and fish appeared. The drawings were produced with great speed, without hesitation or need for correction, and with an amazing confidence for a 61 years old budding artist.

Needless to say, Bressanello had never taken drawing lessons and with such a limited education he had not even benefited from the school’s rudimentary art lessons. There is also no doubt, given his hard and troubled life, that he ever had the time nor the opportunity to previously try his hand at drawing. No one in the family had ever drawn, in fact, all were incredulous when he unexpectedly began to create art.

Bressanello also created small sculptures, which he exhibited with the drawings in the warehouse where he had once stored boats. Tourists began to buy his work and one day, feeling intrigued, a neighbour called Dr. Costantino Garosi, who had a passion for art and parapsychology, stopped to admire the complicated and very original drawings. Talking with Bressanello, Garosi learned more about how the works were produced and immediately identified characteristics of particular interest to him. From the beginning Garosi encouraged Bresanello to continue with the drawings, but to give up the production of the small sculptures, which in his mind had less artistic value. Bressanello, valuing Garosi’s friendship and advice, agreed even though it deprived him of some income.

Benefitting from a retirement pension Bressanello, who was 67 at the time Arte Medianica was compiled, was able to draw full time, with the same will and dedication with which he used to repair his boats. The author was introduced to his work by Dr. Garosi and visited Bressanello several times in his “studio”, where for twelve or more hours a day he was absorbed in his “writing”: which is how he defined his activity. This “writing”, he stated, cost him a lot of effort at first as his hands were used to a completely different kind of work. After a while it became easier and he was able to work for hours and hours at a time.

Bressanello was a simple, honest, enthusiastic and generous man. He drew all day in a picturesque room next to a canal and watched the passers-by admiring his drawings displayed on the pavement. Through a large window he has the panoramic view of a canal and bridge. Only requiring little sleep, he rises at 4 and works for a few hours on a drawing. He then leaves the house for his “studio” where he creates another work. At lunchtime his wife has to go and pick him up, otherwise absorbed by his work, he would not return home for his lunch. In the afternoon he returns and starts again. Drawing for Bressanello is a calming and relaxing activity which makes him happy and is beneficial to his health. It allows him to discharge his repressed tensions, and gives him a great deal of inner satisfaction, balance and serenity. He was at his happiest whilst drawing.

When he began a new drawing he never knew what he would draw. His hand moves, and he feels something inside himself like a voice that tells him, for example, “enough!”, “don’t tangle anymore”, “on that side leave a blank space”, “do not add more”, and so on. When the drawing is finished, even if apparently unfinished, he gets a feeling that he must stop, and if by chance he tries to continue, “the pen” he says, “instead of making lines makes stains.

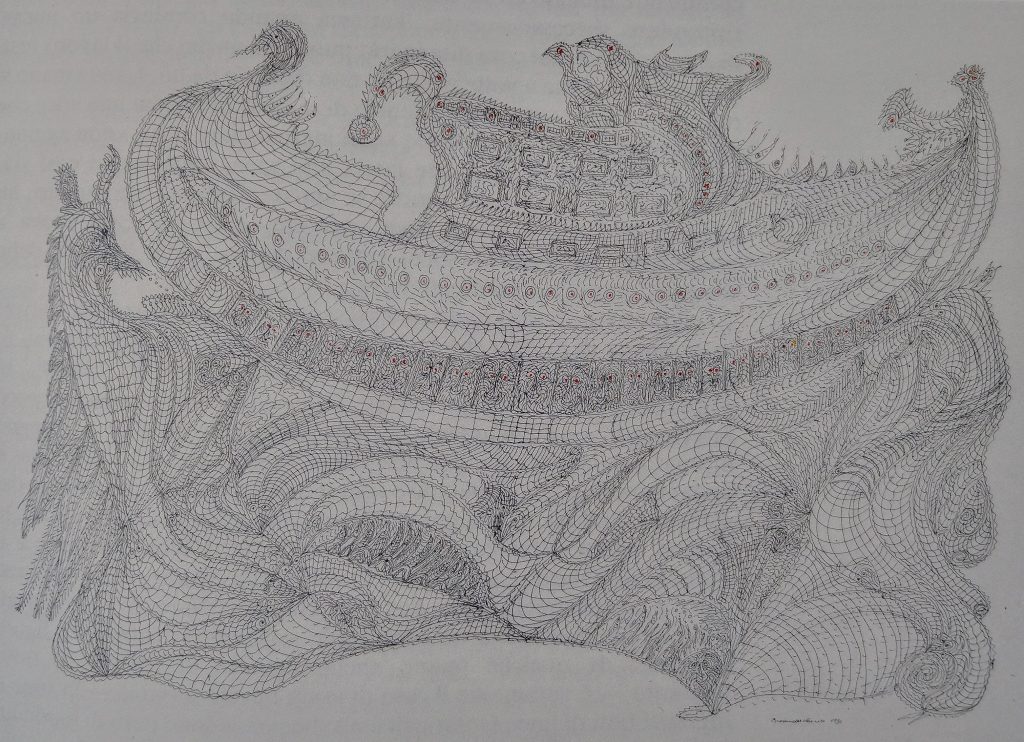

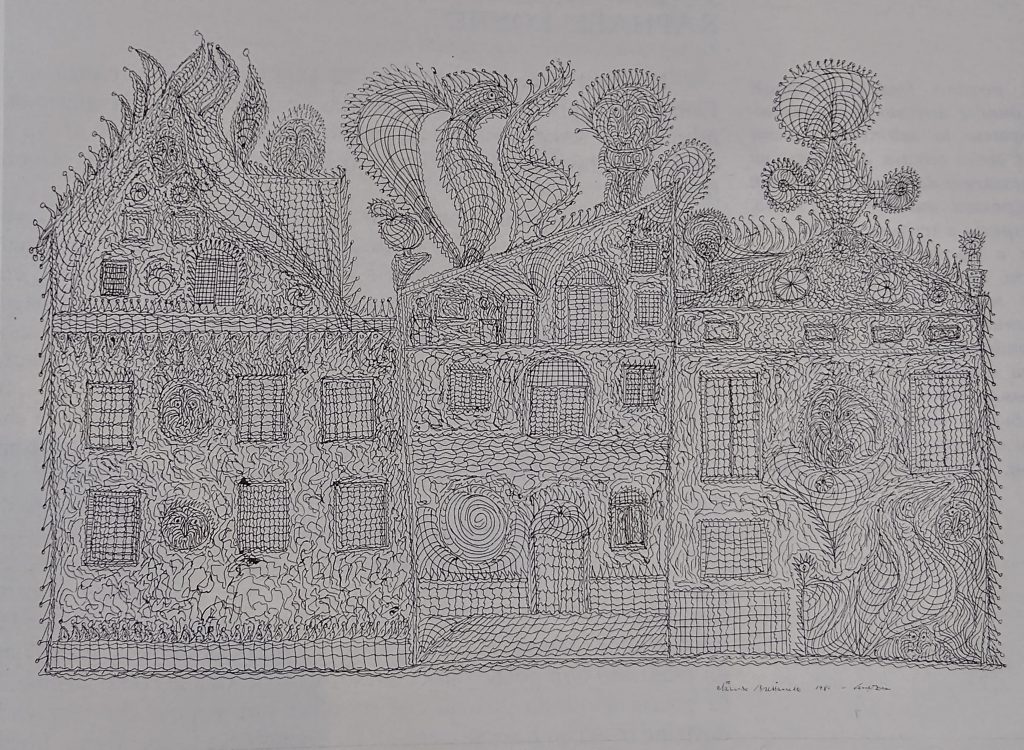

The drawings do not contain a wide range of motifs, but they are presented in ever new ways. In the hundreds of drawings he has done there are no repetitions and to use an expression of Dr. Garosi, they are “variations on the same theme”. It is only when they are completed that Bresanello realised what has appeared on the card and could try to interpret them. What emerges from the drawings is Bressanello’s world: the sea, the nets, the fish, the boats, marine birds, facades of buildings and even the fabulous “Bucintoro” or lion heads that are the symbols of Venice. There are also religious figures, strange hybrid creatures and fantastical fish, that he said, lived in the abyss or who swam in the seas many millennia ago. They are his inner world of extraordinary images, almost dreamlike interpretations of the simple contents of his boatman’s life. All are woven like lace and made of very imaginative lines which still maintain a basic order and symmetry – the memory, perhaps, of the lace made by his mother and the women of Burano, even if the geometric regularity of the lace of Burano is far from the freedom of drawings by Bressanello.

An interesting aspect in Bressanello’s work is his technique. He begins by drawing the outlines at remarkable speed; “I was a carpenter”, he said, “and I’ve always been used to building the skeleton of the boat first and then fills in the structure. Similarly, when he ‘writes’ he does the skeleton or frame of the drawing first, and then fills it with small precise strokes and filigree lines which gradually form his images.

Using markers or ink pens to draw on normal paper or cardboard, Bresanello started with small sheets and then gradually felt the need for more space. Later in his life he drew almost exclusively on large sheets measuring 100 x 70 cm because he said “that’s how it fits everything”. It is worth noting that while the first drawings teemed with obsessive small monsters and heads of all kinds, with the passage of time and the progress of his psychic situation, they became more serene and with an elegance of a consummate artist.

The monochrome drawings achieve the best results with black, blue and red pens on a white background. Sometimes he tries to use coloured markers, but the results are undoubtedly inferior with the plurality of tinted shades taking the charm away compared to the pure lines of the single colour drawings, especially black and white. The same goes for the themes. If Bressanello allows his world to emerge spontaneously the results are remarkable, but the quality is lost if he deliberately chooses what he wants to draw. Bressanello has never tried to give a title to his own drawings, or to comment on them. He may offer a few words such as “This could be a saint or that is a fish without eyes who lived in the abyss”.

What is striking is this man’s joy in performing this activity of his, which offers him practically no income. Every now and then he sells some drawings, but this does not reach the amount he invests in materials which is money he chooses not to spend on any form of entertainment such as the cinema or bar with friends.

Bressanello, unlike some other mediumistic artists, was at first convinced of being the author of his drawings. It did not even occur to him that there was another possible interpretation until Dr. Garosi spoke to him of “automatisms” and of “mediumistic” drawing. Bressanello read more about it and became convinced that his production also had these characteristics, for example, the age at which he started, the technique, the non-participation on a conscious level etc. Through a series of simple séances it became clear that he had a guiding spirit called “Fidelio” who described himself as an ancient Roman who had studied the works of artists who decorated the palaces, but died young and never fulfilled his passion to become an artist like them. It was around the time that Fidelio appeared that Bressanello began to draw facades of buildings. Fidelio also claimed that he was the spirit guide of Léon Petitjean, whose work has similarities with Bressanello. However, this may have been inadvertently suggested after Dr Garosi and Bressanello had seen copies of the French journalist’s spirit drawings.

Bressanello happily accepted the existence and intervention of Fidelio, feeling somewhat reassured and encouraged by his presence. He became a real character to him and was spoken of as a friend. Bressanello also felt honoured by the attention from his family, his small circle of boatmen friends and gondolieri who, after finishing their work, would go to sit silently next to him to watch him work.

Since his mediumistic sessions began, Bressanello began to hear raps in the house and see paintings inexplicably fall from the walls. Objects would move places and the drawing board would lift on its own accord while he was drawing. Bressanello joyfully accepted this strange phenomena as it proved to him the presence of “Fidelio”.

Copyright © Paola Giovetti

For other mediumistic artists featured in Paola’s book please see our pages on Gertrud Emde, Iris Canti, Salomé and Fritzi Libora Reif.