The Moscow Museum of Outsider Art (MMOA) with its collection of more than 4,000 artworks and unique library devoted to ‘non-conventional’ art, has become a recognized centre for collecting, research and promotion of outsider art. One of the artists represented in their collection is Rosa Zharkikh (1930-2015) whose visionary drawings, textiles and even the clothes she wore have left a lasting impression on many people. I felt compelled to find out more and I am grateful to the Museum’s Director, Vladimir Abakumov and Deputy Director, Anna Yarkina for kindly agreeing to an interview so I can share more about their collection and gain an insight into Rosa’s creativity.

Please share more details about your museum collection and how it was established?

The Moscow Museum of Outsider Art (MMOA) started with an exhibition project called “We Create too”, which was launched in 1989. In the landmark ‘perestroika’ period, when thirst for freedom was simply in the air, the young team of the nonprofit organisation, Humanitarian Centre, decided to reveal to a Soviet audience an amazing art phenomenon that, literally and figuratively, had been hidden behind the walls of psychiatric clinics.

An exhibition of 40 artworks by patients of specialized medical institutions was organized at the Museum of Medicine in Moscow. It was a huge success with hundreds of visitors and huge media interest. The willingness of spectators to perceive these new images, radically different from a traditional aesthetic, led to the exhibition project expanding geographically. Exhibitions took place in the republics of the former USSR such as Alma-Ata, Tallinn, Riga and Kiev, and also abroad in Lima, Hamburg, Munich and Dusseldorf. By then, the project included about 300 artworks collected with the help of doctors and relatives of patients who visited our exhibitions. With the far-reaching effects of the media coverage, we began to receive further information on extraordinary cases of artistic expression outside of the ‘traditional’ gallery or museum context which meant the collection continued to grow.

“The thought of creating in Russia a museum collection of artworks, not recognized in the former Soviet Union as fully-fledged works of art due factors such as a lack of training or the mental state of the artists, didn’t leave me.” Vladimir Abakumov – Director of the Moscow Museum of Outsider Art

A pivotal moment came in 1994 with exhibitions at the Creative Growth Art Center in San Francisco and the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne. From that point we knew we wanted to form a museum collection based on the artworks we had amassed and to open a small permanent exposition in Moscow.

We devoted 1995 to analysing the art material we had collected. At that time Russian experts did not pay attention to the phenomenon of outsider art so we focused on foreign research. After a year of painstaking work, it was decided to exhibit the collection (around 2000 pieces) based on four separate sections: Art Brut/Outsider Art, New Invention, Naive Art and psychopathological expression.

Thus, the ‘Outsider Art’ section presented artworks by creators with psychopathological experience who embodied projections of their inner world (Shlyapnikov), visionary artists whose hand was moved by invisible forces (R. Zharkikh), and innocents who did not recognize themselves as artists, but were able to create an ‘alternative reality’ that existed only in their imagination (T. Todorov).

‘New Invention’ was represented by the artists (I. Osipov, I. Blecher, I. Sergeev, etc.) who were closer to the art world than ‘pure’ outsider artists. Not having the high degree of self-sufficiency typical for outsider artists they kept performing adequately in the outer world and trying hard to reveal their art to wide audience. However, the images they created echoed Outsider Art in their originality and expressiveness, demonstrating the ability to impress not only an unprepared museum visitor, but also a professional art critic.

Special attention was paid to artworks of the persons who created “beyond mental health” (M. Paule, E. Sukhachev, Savin). We could not call them outsider artists, as not every individual with psychopathological experience is capable of creating a prominent work of visual art. But a pencil or brush in their hand became a bridge between them and the outer world.

Drawings and paintings classified as “naive art”, which had its own peculiar charm, but lacked spontaneity and extreme originality intrinsic to Art Brut took a particular place in the museum exposition, without claiming to be dominant.

MMOA’s first permanent exhibition opened its doors to the public at the end of 1996 which marked the starting point of the only institution that represented Outsider Art in Russia. It was a small, but very promising space that gave Russians a chance to touch the field of self-expression that went beyond the usual. We continued to push boundaries and were the first in Russia to analyze the special phenomenon of the ‘visionary environment’ – monumental artworks created by visionary artists in their attempts to transform their outer space in accordance with their ideas of a perfect world. In 1999, the wooden sculptures of Alexey Rudov (1926-2002) surrounded by photographs of his ‘open air museum’ and accompanied by Rudov’s stories about the world and about himself became part of the MMOA display.

How was the museum received in Russia? Has outsider art become well known and appreciated by the wider public?

The permanent exhibition was updated in 2000 and we received the attention of professionals such as K. G. Bogemskaya who said “You are ahead of time – this will be recognized in Russia in 10 years.” And she was mainly right. Our display of this unique art phenomenon impressed other professionals too such as O. V. Diakonitsina and V. I. Grozin who was the director of the Museum of Naive Art. We later partnered with the MNA in the organization of the first Festnaiv in Russia. Further promotion of the museum’s amazing creations came from our website being included in ‘Museums of Russia’ from 1997.

However, we did not receive the interest of officials responsible for cultural programmes at that time. Therefore, MMOA developed as a donation-based organization supplemented by grants and fundraising events. The financial support of organizations and individuals was extremely important, but at the same time our private status gave the MMOA the freedom to follow its own exhibition and publication policy.

As a result of the Museum’s activity numerous reports appeared in the media, on the internet and in videos on youtube, as well as on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/outsiderartbrut/). It is too early to talk about widespread popularity of outsider art in Russia as there are only a few permanent exhibitions devoted to this genre of art and the work is not displayed in the best known Russian museums. However, with regard to the MMOA’s mission to create awareness of outsider art in Russia, it has been successful. The Museum has drawn the attention of a wider audience to the amazing phenomenon of spontaneous creativity from talented self-taught artists who create exclusively for themselves, not recognizing their drawings, paintings and objects as art. It was the first institution in Russia to grant these creators and their works the right to recognition. Nowadays others follow in the Museum’s steps, but it will forever remain the first.

Did the outsider art/art brut establishments abroad play a part?

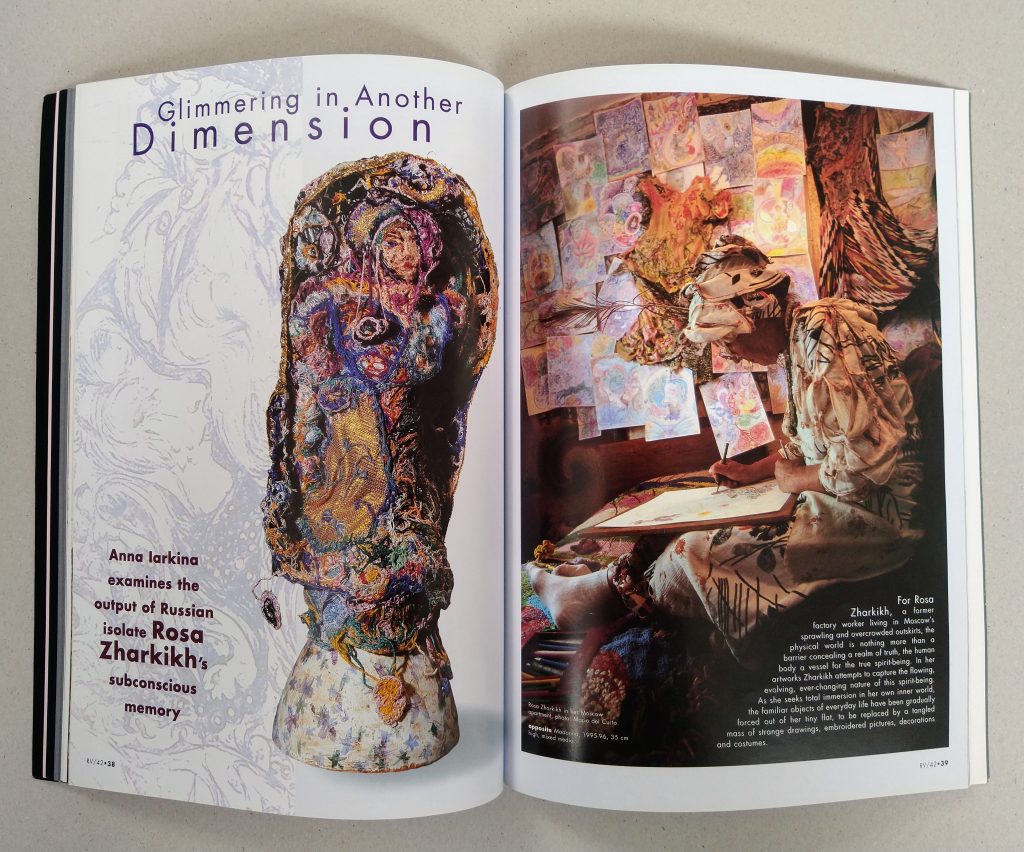

Articles about Russian outsider artists began to appear in foreign publications and revealed to the world artists such as Rosa Zharkikh (Raw Vision #42, 1998) and Alexey Rudov (Raw Vision #50, 2002). Nowadays they are recognized as classics of Outsider Art. In 2002 MMOA was included in Raw Vision’s Outsider Art Source Book, which presented the most significant institutions and names in the field of Outsider Art.

Also, one of the most important tasks of the museum was to replenish the collection. It was realized by our own search for talented self-taught artists and ‘external’ donations, as well as the exchange of artworks between MMOA and international museums and collections. We aimed to present a maximum possible range of artworks by both Russian and foreign outsider artists who each created their amazing and deeply individual universes.

We cooperated with Michel Thevoz, writer, art historian, curator of the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne (1976-2001), Lucienne Peiry, Director of the Collection de l’Art Brut (2001-11), John Maizels, founder of Raw Vision magazine, Roger Cardinal, scholar and author of Outsider Art, John M. MacGregor, Professor of psychology of art and author of Discovery of the Art of the Insane, Dr. Johann Feilacher, Director of the Art Brut Center Gugging, Dr. Thomas Roske, Director of the Prinzhorn Collection Museum in Heidelberg, Caroline Bourbonnais, founder of the La Fabuloserie Museum, Laurent Danchin, writer and specialist in Art Brut, Outsider Art, and Singulier Art, Martine Lusardy, Director of the Halle Saint-Pierre, and many, many others. Close contact with our colleagues abroad gave us a chance to exhibit in Russia not only the peculiar embroideries by Rosa Zharkikh, drawings by Evgenia Kasatkina and Alexander Lobanov, paintings by Todor Todorov and Nikolai Kozlov, etc., but also art works by Madge Gill, Michel Nedjar, Chris Hipkiss and Martha Grunewaldt. The Collection now has over 4000 works of art.

How did you hear about the work of Rosa Zharkikh and when did you acquire the works for the museum? How many drawings and embroideries do you have in the collection?

Anna Yarkina: We were told about the strange drawings and embroideries of a lonely woman from a documentary filmmaker who was a visitor at our permanent exhibition in 1996. She told us that while working on one of her films, she met a strange woman who drew unusual images and kept her drawings under a mattress.

An hour-long journey to the outskirts of Moscow ended with a knock on a battered door. After long negotiations and introductions, the hostess finally decided to let us into the apartment, after dragging a rather large black mongrel from the door. We went through a dark, narrow corridor and got into a small, shabby room, where we stared in amazement: wonderful intricate embroideries hung on the walls, crookedly pinned to the wallpaper.

Rosa agreed to show us her drawings hidden in her nightstand and under the mattress. Many of them were already 20 years old by that time, but Rosa did not consider them as art objects, and almost never showed them to anyone. So it was a miracle to find out about their existence. We had a long talk about Rosa’s hard fate, about the origins of her work and her attitude to them. We told Rosa about our museum, our goals and objectives, and then asked for several works for the exhibition. We realized that it would be difficult to persuade her to part with them, since they formed a microcosm that surrounded her with reflections of her ‘parallel world’. However, negotiations resulted in the opportunity to exhibit several of Rosa’s drawings and embroideries in the MMOA’s permanent exhibition at the end of 1996, and in 1997, their ‘exhibition march’ around the world began including Slovakia, South Africa, Russia, Serbia, United States, Finland, Greece, France, Switzerland, Norway and Montenegro.

As Rosa’s trust in the Museum grew and her creative potential continued to develop, she agreed to give us her artworks on a permanent basis. The space of her small apartment was never empty and as some of her creations went out into the big world they were immediately replaced by new ones that appeared, according to Rosa, ‘by themselves’, as a result of her intermittent visions. Through this constant replenishment she was able to preserve her creative aura and the integrity of her microcosm.

The MMOA collection presently includes 240 art works by Rosa Zharkikh of which 80 are embroideries.

Is it unusual to find Russian female visionary artists like Rosa, are there others similar to her in your collection?

The probability of the phenomenon of a female visionary artist in Russia is the same as in other parts of the world, since manifestation of an extraordinary gift does not depend neither on the will of the person to whom the gift is granted, nor on his or her external environment. As for the probability of discovering such a creator, we should talk about the presence of institutions engaged in searching for outsider artists in a particular country of the world, and about the extent of awareness of a general audience about the value of visionary art. In Russia, the number of such specialists and organizations is small, but due to the advanced level of a media field and digital technologies, this number is quite enough to draw attention to any case of extraordinary self-expression. If we talk about artworks by female visionary artists in the MMOA collection, we can mention Madge Gill and Katyusha (Ekaterina Skvortsova).

Is Rosa’s art well known and appreciated in Russia?

Rosa Zharkikh is one of the most popular outsider artists in Russia. Her work continues to fascinate and arouses the desire to comprehend its origins. Her name is well known to any specialist in the field of Outsider Art, and to any person who ever visited MMOA. As has been said, prior to forming the MMOA collection, Outsider Art in Russia was unknown to both the general audience and even most specialists. There were no publications in Russian devoted to the topic and no exhibitions. There was just no information available which is why we considered the promotion of Outsider Art as the main mission of the MMOA and our goal has mainly been achieved with a lot more people now aware of the Outsider Art phenomenon and artists like Rosa.

Tell me a little more about Rosa’s life? When did she begin to create her visionary artworks and why?

Born in Moscow in 1930, Rosa’s early life was typical of the Soviet-era working class. Although she came from an educated family (her mother was a teacher and her father an engineer), Rosa dropped out of high school and graduated from a vocational school that specialized in training blue-collar workers. For all of her adult life, Rosa worked as a repair and maintenance specialist in heavy-machinery factories – first in the provincial town of Vladimir and later just outside Moscow. At the height of the Soviet era, this was a lonely and monotonous existence. Rosa spent most of her day on the factory assembly lines, where the dirt, gloom and dust were relieved only by the occasional flare of a blowtorch or the small fires that workers built to keep warm. Never married, Rosa returned alone in the evenings to Moscow’s working class suburbs, where she lived in a cramped apartment overshadowed on all sides by concrete high-rise apartment blocks.

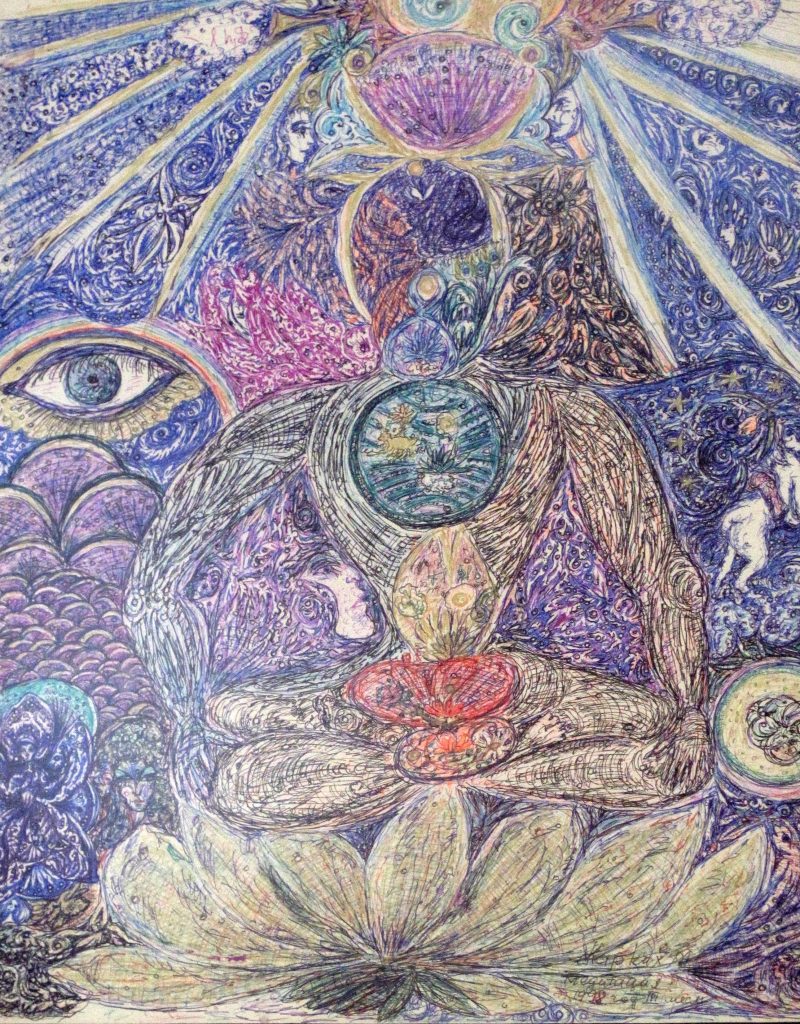

To trace the history of Rosa’s life as an artist, we need to go back to 1976. In that year, she became severely ill and underwent a series of operations. Unable to cure her illness using more traditional means, her doctors eventually gave her a full blood transfusion. Rosa dates her creative impulses from this event. During her lengthy recovery in the hospital, Rosa began to draw. Or, as Rosa herself describes it, her hands began to draw, seemingly of their own volition and directed by an invisible force. It was clear to Rosa that the emerging images were self-portraits, but self-portraits of an ideal self, living in a harmonious ‘parallel’ world that existed only for her. Since then, Rosa has been creating art almost all the time.

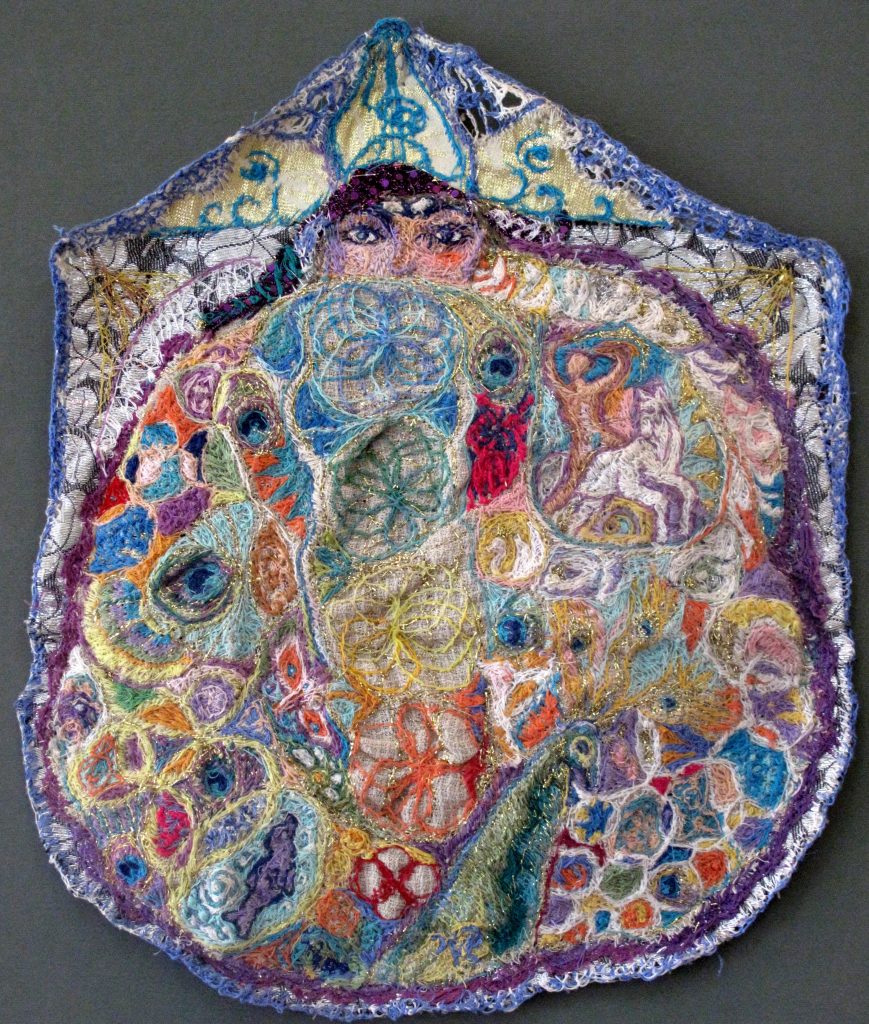

Her drawings are characterized by haunting graphic symbols embedded in flowing designs. Wonderful shapes, such as graceful flowers and waves, migrate from one drawing to another, creating a sense of continuous movement throughout her work. Soon after starting to draw, Rosa also began to create embroideries. These elaborate works, which include dresses, book covers and tapestries, typically take her several years to finish and are inspired by dreams where she sees petal-like images “glimmering in another dimension.” Despite the beauty of her works, Rosa rarely refers to her pictures and embroideries as artworks, calling them instead her ‘children’.

They were obviously very precious to her and she had kept her creativity a secret from the world for such a long time. How do you think she felt about public recognition and about her work being exhibited?

She did not show her drawings and embroideries to almost anyone for the first 20 years of her spontaneous creativity, until the moment we discovered them almost by chance. Rosa created her ‘children’ under the influence of the need to depict images she perceived through her visions. And the recognition that she obtained as a result of her cooperation with MMOA did not change things. The source of her creativity remained the same — the artist’s inner world, which broke out in the form of images captured unconsciously and spontaneously. Her time-consuming embroideries were no exception, she could only work on them at the moment of inspiration.

Rosa was very concerned about parting with her creations, especially the embroideries which were laboriously created, and the idea of exhibiting them. They were not works of art to her, having a specific artistic value. Instead, they were of absolute value to her personally. Gradually she got used to the thought of a part of her ‘parallel world’ being exhibited in our museum. We brought Rosa to see the MMOA’s permanent exposition and showed her the new home for her artworks. We also informed her about any steps on promoting her creations. We were a little bit afraid that popularity could destroy the basis of the artist’s creative process by generating the temptation to produce works ‘to order’. But, fortunately, Rosa’s irresistible need to materialize her visions did not depend on the number of exhibitions, nor the official status of ‘artist’ – she was just overflowing with images.

What about attention from the media?

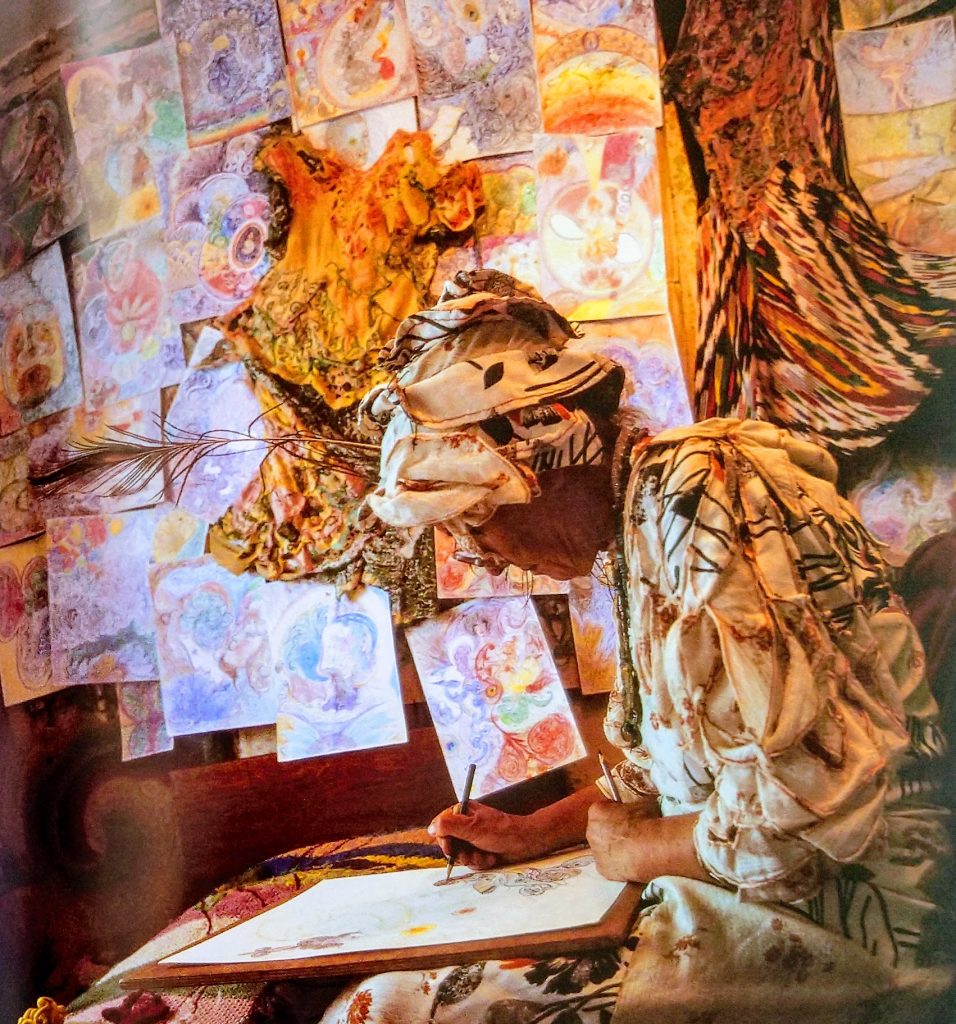

After our first visit we avoided visiting her too often, as it was imperative that nothing disturbed the solitude necessary for her life and creativity. At the same time, the journalists who wrote and made videos about the museum, about outsider artists and relevant events, repeatedly asked us to arrange a meeting with Rosa. However, the artist showed no desire to have guests in her apartment. The exception was made only once — for the Swiss photographer Mario Del Curto, known for creating photographic portraits of the most famous outsider artists. He immersed himself in the atmosphere of the artist’s environment and took a few pictures, which were later used as illustrations for the article in Raw Vision.

During the photo shoot, we met some difficulties; the apartment was so small and filled with various art objects created by Rosa, that it could hardly accommodate four people standing up. The dog — the only friend and ‘family’ of the hostess was also not friendly towards the guests. However, the pictures taken that day became the most widely known photographic portraits of the artist. One of them captured Rosa at work, although it could hardly be a complete creative process then – for pure creativity, she needed solitude that facilitated immersion in her inner world.

Did she have any particular rituals or a place/time she liked to work?

Her visions came spontaneously, and she immediately put the fleeting images into drawings. Sometimes they formed a memorable picture, which Rosa eventually embodied in the form of embroidery in times of creative inspiration. She didn’t have a specific place in her apartment nor a certain time of day that were most favorable for producing pieces of art. The creative impulse could catch her at any time.

How did her family feel about her art?

Rose was a lonely person. Her parents and sister died long before we met her. She created solely for herself, guided by her own opinion, her inner impulses and her perception of the world.

Was she interested in the work of other visionary artists? For example, Madge Gill, who is also in your collection.

Rosa was quite indifferent to the self expression of other mediums, although she had seen their artworks exhibited in our museum. True outsider artists stand out from art society as they focus on their own inner world, while the external one with all its manifestations, including creative work of other people, is secondary to them. Parallel universes of other visionary artists did not cause a strong emotional response, deep interest or any influence for Rosa.

Can you tell us more about Rosa’s parallel world and the visions she experienced? Did she believe she was guided by an invisible entity?

Unlike some other visionary artists, Rosa did not follow any specific ‘instructions’ from a strange guru, did not hear voices, and did not embody other people’s ideas in her visions. The philosophy of her life and her creativity developed and transformed throughout the entire period of her artistic expression. She believed her purpose was to create a bridge between two worlds which were equally important to her: the real one and a parallel one. Also, the idea to perceive the nature of this bridge never left Rosa. And while she was searching for answers by referring to a variety of sources from traditional world religions to mystical teachings and scientific concepts, echoes of her search can be found in the amazing images of both the ‘permanent inhabitants’ of the ‘parallel world’, and the artist herself.

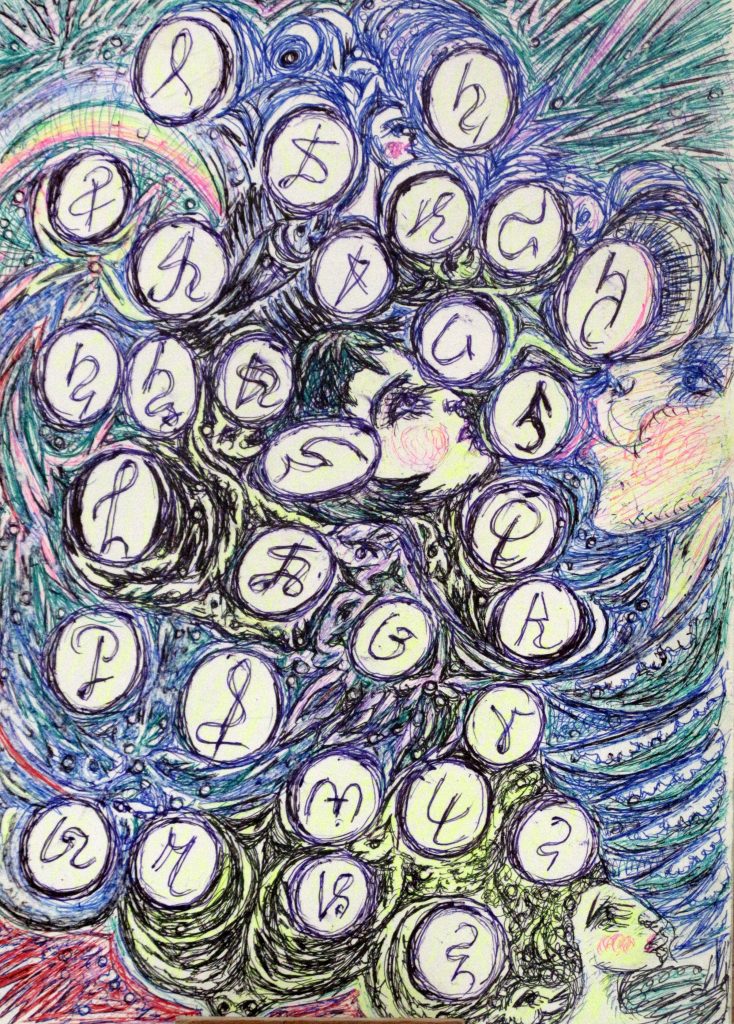

When asked about her art, she explains that she draws as part of her personal struggle for spiritual purity and reconciliation. For Rosa, the concept of struggle is central to her work. Although her drawings appear dreamlike and spontaneous, they are actually the result of a never-ending effort to capture visions and feelings that are by their very nature unstable and fleeting. As part of this struggle, Rosa is constantly seeking out new materials and techniques in order to more accurately depict the atmosphere of her inner world. Thus, the monochromatic interlacing lines (usually drawn with an ordinary ballpoint pen) that were characteristic of her early works gradually evolved into the colourful threads of her embroideries – the medium that Rosa believes represents the pinnacle of her work, and the most perfect solution she found for her creative quest.

For Rosa, the parallel world is a brightly coloured and well-populated word that radiates light and joy. Miniature temples and pagodas with cupolas are scattered across the landscape of her work. Processions of people in white clothes echo mysterious visions that Rosa recalls from her youth. Her human images are usually female, often graceful and tranquil faces that symbolize Rosa’s own presence in the parallel world. Some observers have noted that the world depicted in Rosa’s work is reminiscent of the ‘kingdoms of rest’ that are sometimes described by people who meditate deeply or have been clinically dead. Indeed, this similarity suggests that the roots of Rosa’s art may lie in visions that she saw during her illness – visions that were recorded in her subconscious memory.

Rosa calls the human figures in her work “pseudo-heroes.” Idealized by their creator, these figures inhabit the higher circles of the parallel world. Some of them symbolize people who have renounced a sexual life. Others are images of people from Rosa’s own life, such as her mother and a young girl who represents the soul of her late sister. These people are heroes because they have succeeded in realizing a perfect world – a world that can only be attained through constant self-improvement and spiritual purification.

How did she describe her spirituality?

In an effort to return more often and more fully to her newfound parallel world, Rosa in the 1970s became interested in religion, especially Buddhism. In those days, almost no information about religion was available in the Soviet Union due to the regime’s strict adherence to official atheism. Nevertheless, Rosa managed to pick up bits and pieces of information and became attracted to the idea of reincarnation which Rosa described as the hope that she, in some form, will walk on the green grass of a purer world in the future. Also around this time, Rosa taught herself a form of simple meditation. In the 1990s, as more information about the outside world became available in Russia, Rosa became fascinated with other Asian religions, including Hinduism and Tibetan Buddhism.

The vitality of Rosa’s art and her personal spiritual quest over the years have been accompanied by a growing reclusiveness from ordinary life. By committing to self-purification Rosa avoided what she regards as the corrupt trappings of modern civilization. She refused to watch television, followed strict diets, and tried to minimize her communication with other people which led to friends falling away. Rosa refused to show her artwork because she believed that most observers could not understand the significance of her work. This extreme reclusiveness even affected the nature of her art, as the embroideries hanging on her walls and growing collection of drawings and objects ran out of space. Pinned in overlapping layers on the walls, the threads of her embroideries tangled up over the years, gradually merging and separating the individual works – like some kind of living organism shifting and changing of its own accord.

Some of her works have symbols and messages in them. Did she explain the meaning behind these? Was she surprised at what she was able to produce?

Rosa was unwilling to reveal the meaning of the mysterious messages that are scattered throughout her drawings. Part of them are based on the alphabet invented by Rosa herself – they were clear to her only. Besides these, there were the inscriptions which even Rosa could not interpret. We can also find echoes of mythology and the teachings that the artist ‘studied’ in her peculiar way and adapted to her own ideas. For instance, Zodiac signs and symbols of the world’s religions. She never sought to give a detailed interpretation of her work. Some drawings became a revelation even to Rosa, as she created them spontaneously and could only partially explain their meaning. In her later works, colours took on a special meaning, symbolizing specific characters or expressing certain aspirations and ideas

Can you tell us more about the techniques that helped her create art such as her meditation?

In the last years of her life, Rosa was interested in ghost theories of energy fields, the relationship between spirit and reality, and even echoes of some of Nikola Tesla’s ideas. From her personal perspective and through the lens of her visions, she tried to comprehend the ‘bridge’ between the real world and the ‘parallel’ one revealed to her in the process of meditation. She locked herself in her apartment, where the temperature in winter did not exceed 15 degrees celsius, and, with an effort, as her eyes were weak, read the books she occasionally acquired. Illustrations of Nikola Tesla’s devices and his field of energy work were extremely interesting for Rosa. She ‘received information” and then completely devoted herself to self-reflection and spontaneous creativity. She tried to get answers to her questions in the drawings and embroideries she produced.

How did she title her artworks?

Finding that most of her works are impossible to name, Rosa often defined them in terms of concepts that come close to their meaning. Some of these concepts draw on Christianity – such as one work called ‘Madonna’ (1996) and an embroidered book cover that she calls a ‘Bible’ cover. One of her relatively few sculptural works is an embroidered doll with a mirror in its back – so, as Rosa explains, people can see “themselves and the Angel simultaneously.” Other works she links to Asian religious symbolism, such as drawings called “Dragon” (1976) and “Lotus” (1977). Some of her works are more directly expressive of Rosa’s ideas about dual worlds and the spiritual life. “The Stages of Going Up” (1998), for example, depicts a series of complex interactions between a lower world, populated by insects and birds, and a superior world, where human beings and the Gods live. Another work from the 1990s, “Karmic Stream” (1999), depicts the evolution of consciousness.

Rosa’s embroideries and drawings are exquisite. I notice that there are some clothes too. Did she ever wear her own creations? Was drawing or embroidery more important to her? Where did she find her materials?

Rosa liked to wear her own dresses. Guided by her visions, she made them up of ‘petals’ which she cut off any fabric available. By donning this attire, Rosa, in her opinion, was closer to the ‘parallel world. It was as if she stood on the border of the worlds. She felt herself to be more authentic if her own creations replaced ordinary clothes. Sometimes she added a bizarre self made headdress or an embroidered handbag to her outfit. It was in this garb when she met Mario Del Curto. Since the petal-like garments appeared in the artist’s visions as if they were hovering in the fourth dimension, we decided to recreate the effect of floating or flying when exhibiting Rosa’s dresses in MMOA by hanging them in a special way.

Before Rosa met us, she used only improvised materials for her work: battered notebook sheets, ordinary ballpoint pens, tangled threads, pieces of old cloth, clay things. Our friendship with the artist changed this a bit. At Rosa’s request, we helped her purchase art materials and supported her search for new techniques. So today we can find drawings made with helium pens and coloured pencils, as well as embroidery with special threads among Rosa’s artworks. She considered all the materials just as a means by which she embodied her visions, with no difference in critical value between the ‘initial’ and the ‘latest’ materials. The image itself was at the core and it was primary.

Creating embroidered works was more important to her than capturing images on paper. According to Rosa, the volume and softness inherent in her embroideries conveyed the harmony of her ideal world in the best way, and the long period needful to create such works gave the chance to depict images that appeared at different times, in different states.

Did she work on her art everyday? How long would it take her to create each piece?

Rosa’s creative activity was incompatible with planning. Her visions came to her spontaneously to be either immediately (for drawings) or gradually (for embroideries) embodied in the material. And if a small drawing, on which Rose tried to work as quickly as possible to capture the disappearing images, took up to a few hours of her time, her work on embroidery could take from six months to several years. Rosa herself could not even predict the time of completion of a particular work — it depended on interaction between two worlds she lived in.

Did her art bring her comfort and contentment?

After a mysterious force made Rosa draw, artistic expression became the meaning of her life. It brought her inner harmony rather than physical comfort. Through meditation and immersion in the creative process, Rosa could ‘transfer’ herself to her ideal world – beautiful, bright and calm. Everyday problems receded into the background, loneliness disappeared – they left room for self-improvement and self-discovery.

As custodians of Rosa’s legacy, what would you like to see in the future for her artworks? Are there any exhibitions or publications planned? What’s next for MMOA?

As for the further promotion of the legacy of Rosa Zharkikh, we would be happy to present her amazing works to as many people as possible, all around the world, both in the form of traditional exhibitions and in an online format. Modern means of communication make it possible to organize virtual exhibitions, which have now become relevant more than ever during the pandemic. They can bring art and culture, independent of borders and restrictions. And they will certainly be in demand after the pandemic is ended. At the same time, we are deeply convinced that direct contact with pieces of art provides the most complete perception of creative works – especially if we talk about embroidery or three-dimensional objects. Therefore, traditional exhibitions, including international ones, are important for our mission.

The permanent exhibition of MMOA in Russia was open to the public until 2011 when, due to the absence of regular funding for the museum activities, its collection was moved to Montenegro where it became the basis for opening an Outsider Art Centre in Bar. Since then artworks from the collection have been presented in various exhibitions, including Norway, France and Serbia, and continue to delight audiences. The latest exhibition was in 2020 in Pljevlja (Montenegro).

It is our big wish to open a museum of Outsider Art in Montenegro. Then art works by Rosa Zharkikh would take their rightful place in a new permanent exhibition. We are also open to cooperation with relevant organizations and internet resources in the promotion of both the creative legacy of Rosa Zharkikh and other artworks from the collection.

This interview took place March-April 2021

Further details about Rosa can be found in the article Glimmering in Another Dimension by Anna Yarkina (Deputy

Director of MMOA) published in Raw Vision #42, 1998. The permanent exposition in Moscow was closed in 2011. The MMOA collection is currently represented by the Outsider Art Center in Bar, Montenegro.